Introduction:

This is the guide for software developers and testers to understand and start working on the very famous

Agile SCRUM methodology for software development and testing. Learn the basic but important terminologies used in Agile Scrum process along with a real example of the complete process.

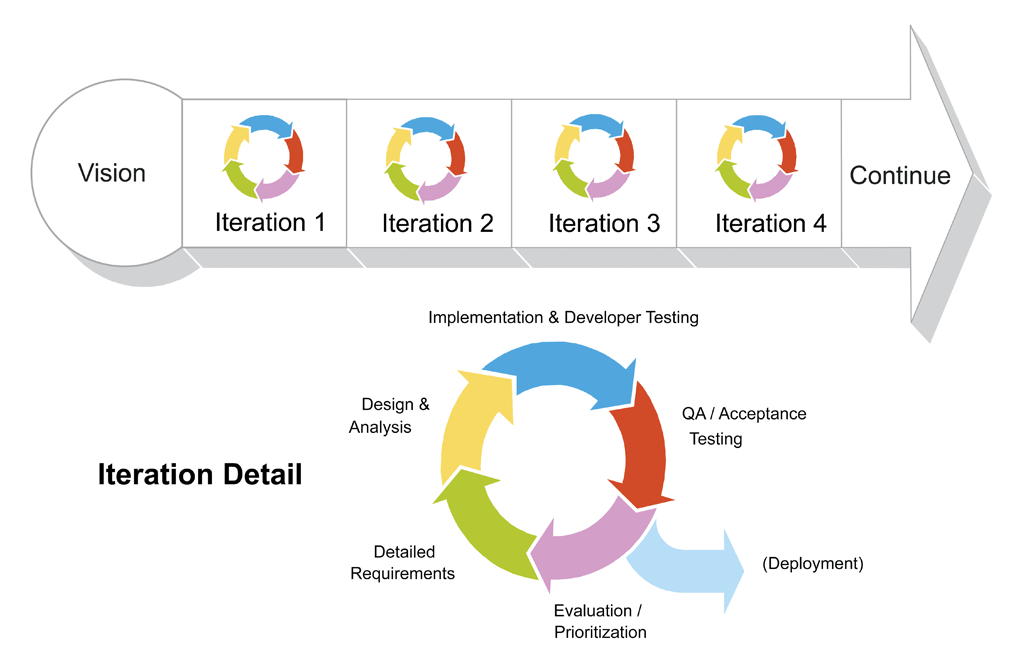

SCRUM is a process in agile methodology which is a combination of Iterative model and incremental model.

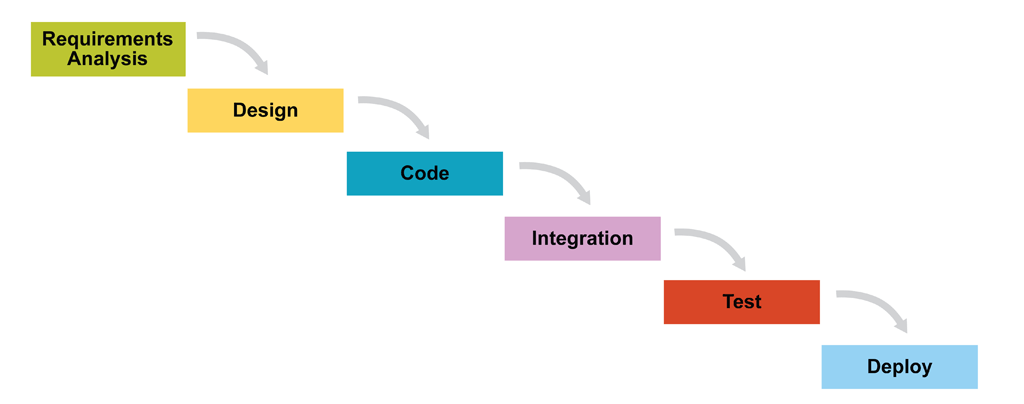

One of the major handicaps of the traditional water-fall model was

that

– until first phase is complete, the application does not move to the

other phase. And if by chance there are some changes in the later stage

of the cycle, it becomes very challenging to implement those changes, as

it would involve revisiting the earlier phases and redoing the changes.

Some of the key characteristics of SCRUM include:

- Self-organized and focused team

- No huge requirement documents, rather have very precise and to the point stories.

- Cross functional team works together as a single unit.

- Close communication with the user representative to understand the features.

- Has definite time line of max 1 month.

- Instead of doing the entire “thing” at a time, Scrum does a little of everything at a given interval

- Resources capability and availability are considered before committing any thing.

To understand this methodology well, it’s important to understand the key terminologies in SCRUM.

Important SCRUM Terminologies:

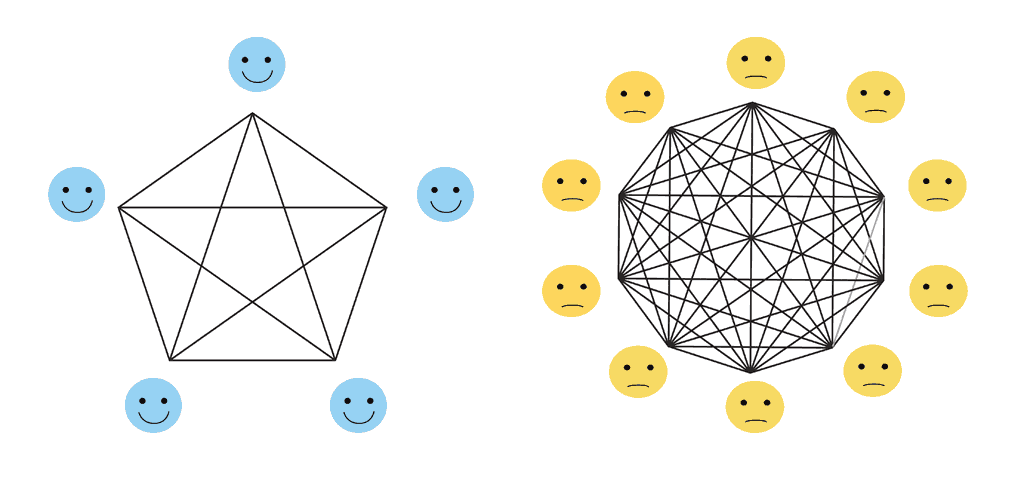

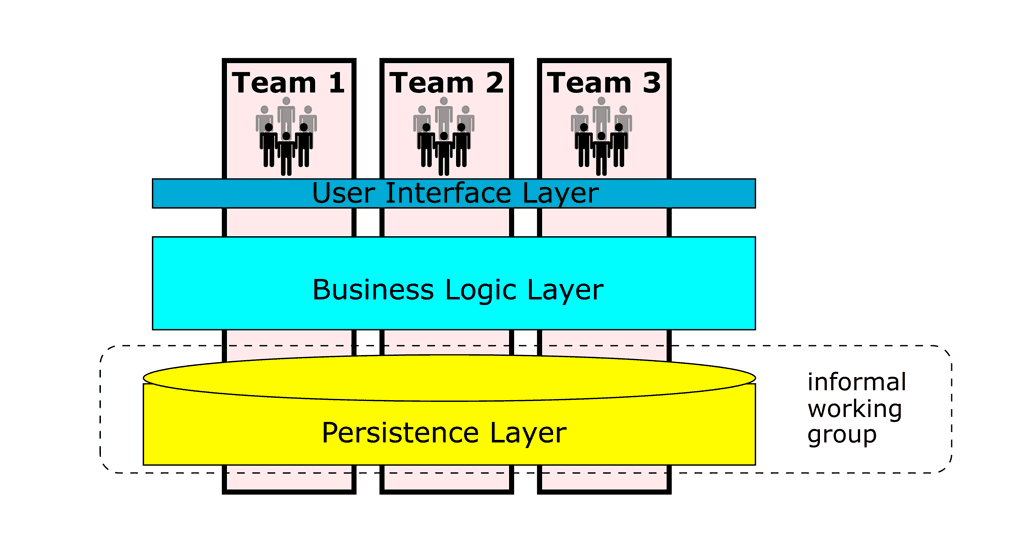

1. Scrum Team

Scrum team is a team comprising of 7 with + or – two members. These

members are a mixture of competencies and comprise of developers,

testers, data base people, support people etc. along with the product

owner and a scrum master. All these members work together in close

collaboration for a recursive and definite interval, to develop and

implement the said features.

2. Sprint

Sprint is a predefined interval or the time frame in which the work

has to be completed and make it ready for review or ready for production

deployment. This time box usually lies between 2 weeks to 1 month. In

our day to day life when we say that we follow 1 month Sprint cycle, it

simply means that we work for one month on the tasks and make it ready

for review by the end of that month.

3. Product Owner

Product owner is the key stakeholder or the lead user of the application to be developed.

Product owner is the person who represents the customer side. He /

she have the final authority and should always be available for the

team. He / she should be reachable in case any one has any doubts that

need clarification. It is important for the product owner to understand

and not to assign any new requirement in the middle of the sprint or

when the sprint has already started.

4. Scrum Master

Scrum Master is the facilitator of the scrum team. He / she make sure

that the scrum team is productive and progressive. In case of any

impediments, scrum master follows up and resolves them for the team.

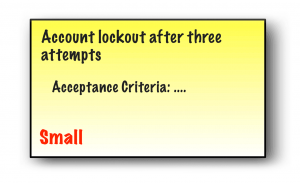

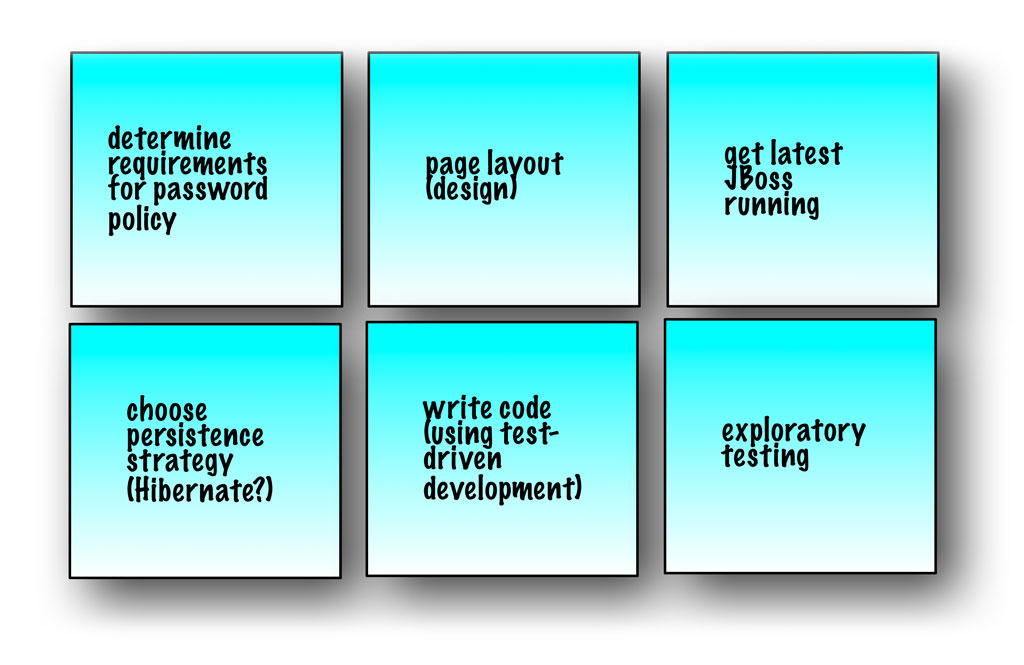

5. User Story

User stories are nothing but the requirements or feature which has to

be implemented. In scrum, we don’t have those huge requirements

documents, rather the requirements are defined in a single paragraph,

typically having the format as:

As a <User / type of user>

I want to <Some achievable goal / target>

To achieve <some result or reason of doing the thing>

For example:

As an Admin I want to have a password lock in case user enters

incorrect password for consecutive 3 times to restrict unauthorized

access.

There are some characteristics of user stories which should be

adhered. The user stories should be short, realistic, could be

estimated, complete, negotiable and testable.

Every user story has an acceptance criterion which should be well

defined and understood by the team. Acceptance criteria details down the

user story, provides the supported documents. It helps to further

refine the user story. Anybody from the team can write down the

acceptance criteria. Testing team base their test cases / conditions on

these acceptance criteria.

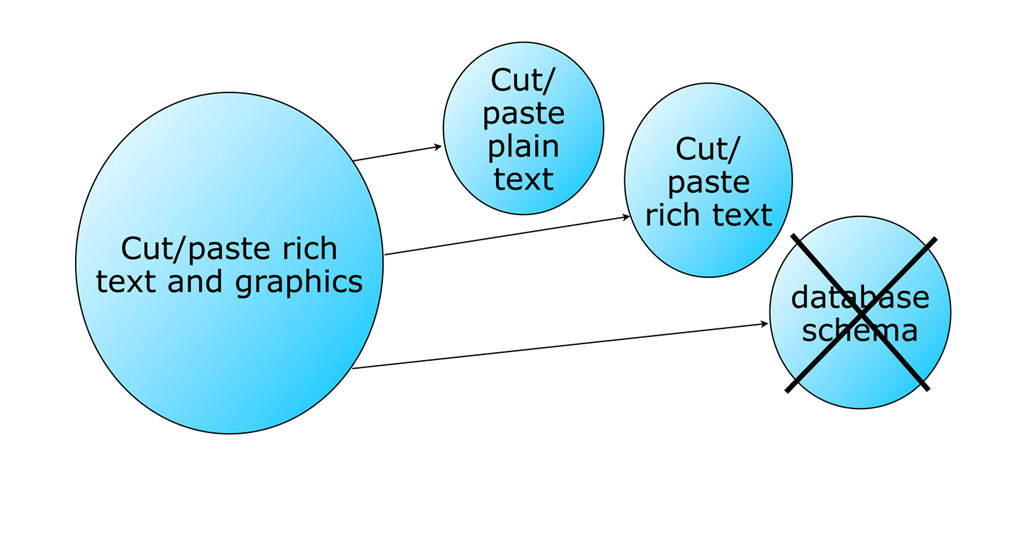

6. Epics

Epics are equivocal user stories or we can say these are the user

stories which are not defined and are kept for future sprints. Just try

to relate it with life, imagine you are going for a vacation. Since you

are going next week, you have everything in place like your hotel

bookings, sightseeing, travelers check etc. But what about your vacation

plan for next year? You have only a vague idea that you may go to XYZ

place, but you have no detailed plan.

An Epic is just like you next year’s vacation plan, where you just

know that you may want to go , but where, when, with whom, all these

details you have no idea at this point of time.

In a similar way there are features which required to be implemented

in future whose details are not yet known. Mostly feature begins with an

Epic and then broken down to stories which could be implemented.

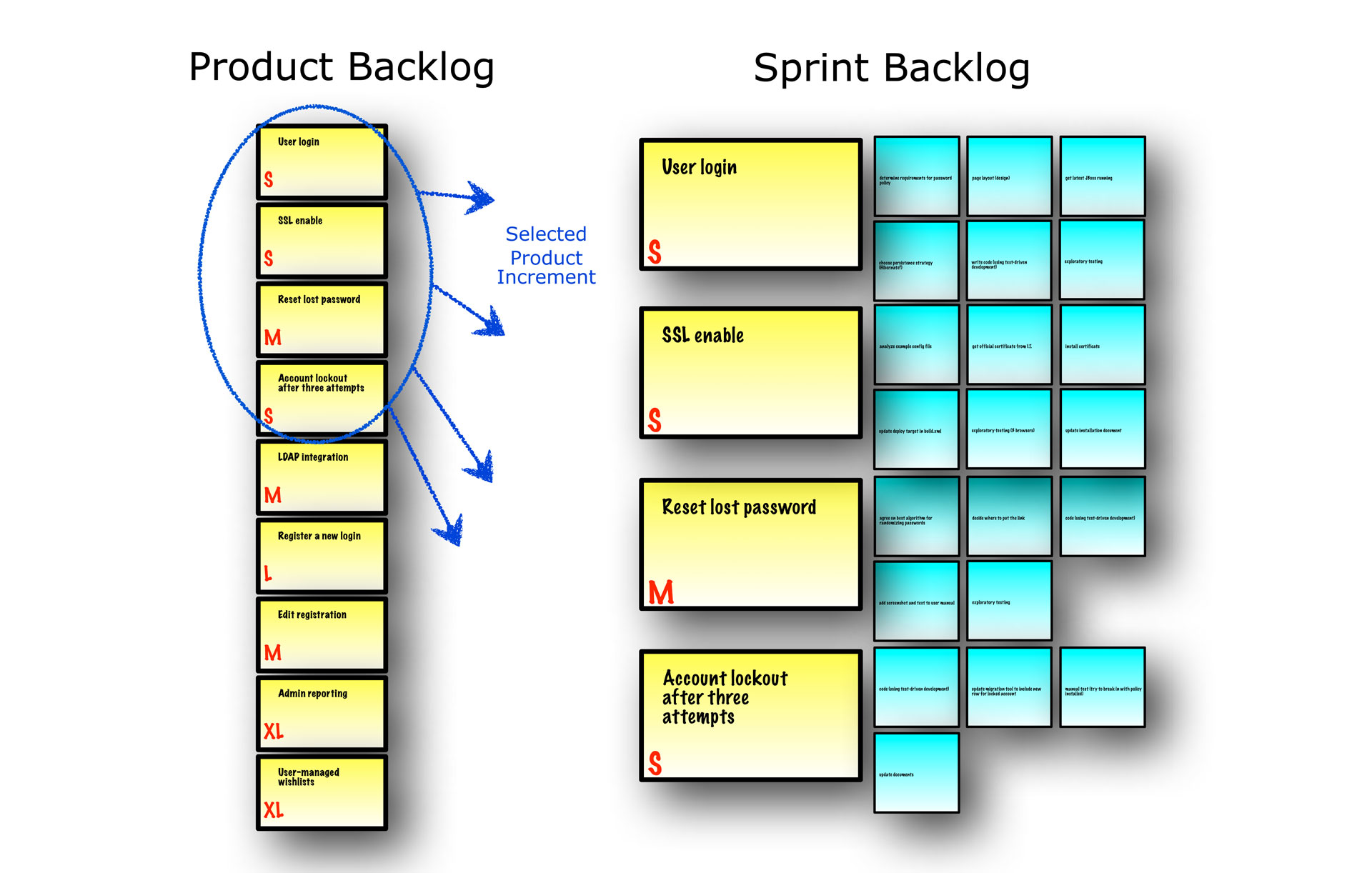

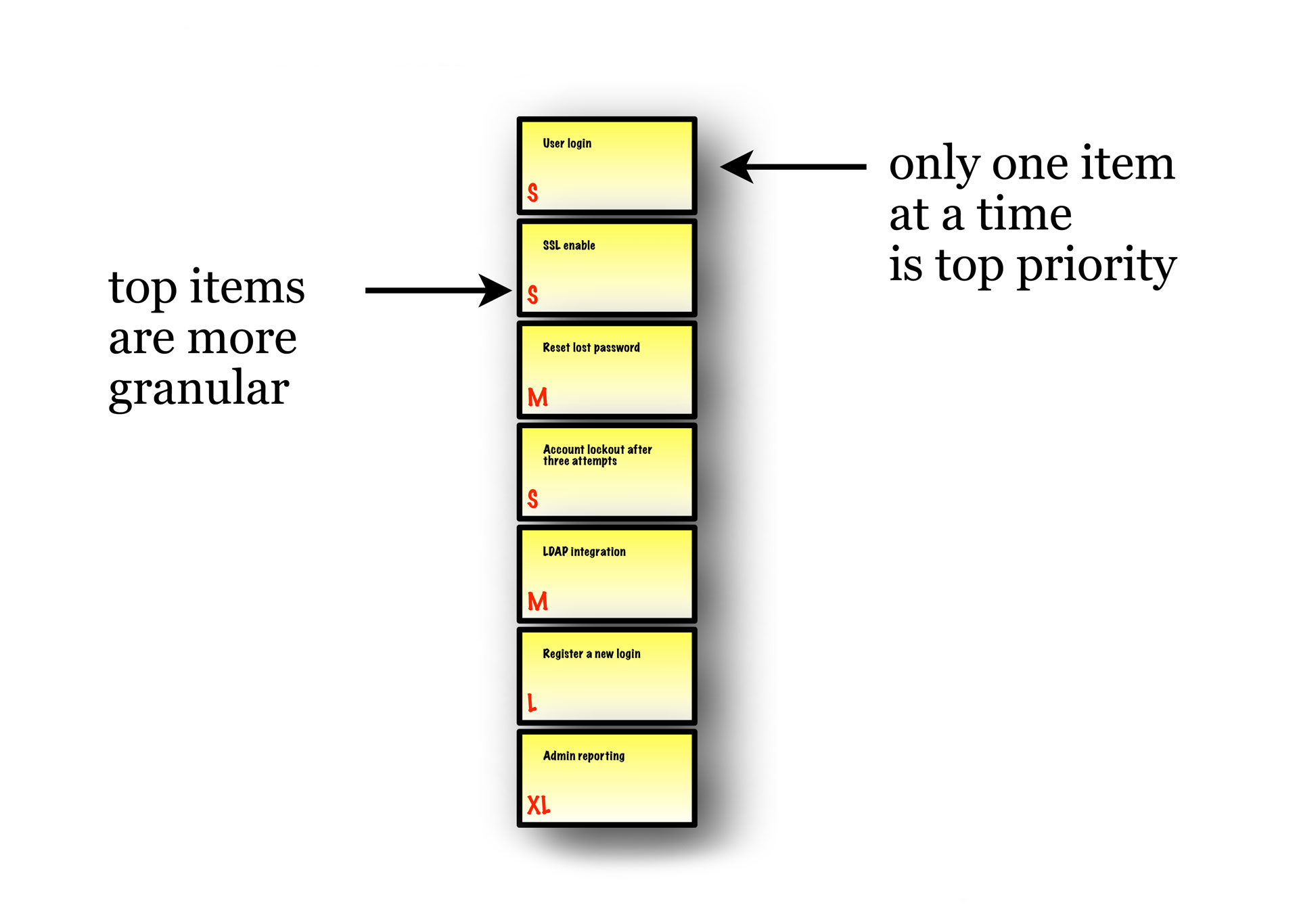

7. Product Backlog

Product backlog is a kind of bucket or source where all the user

stories are kept. This is maintained by Product owner. Product backlog

can be imagined as a wish list of the product owner who prioritizes it

as per business needs. During planning meeting (see next section), one

user story is taken from the product backlog, team does the

brainstorming, understands it and refine it and collectively decides

which user stories to take, with the intervention of the product owner.

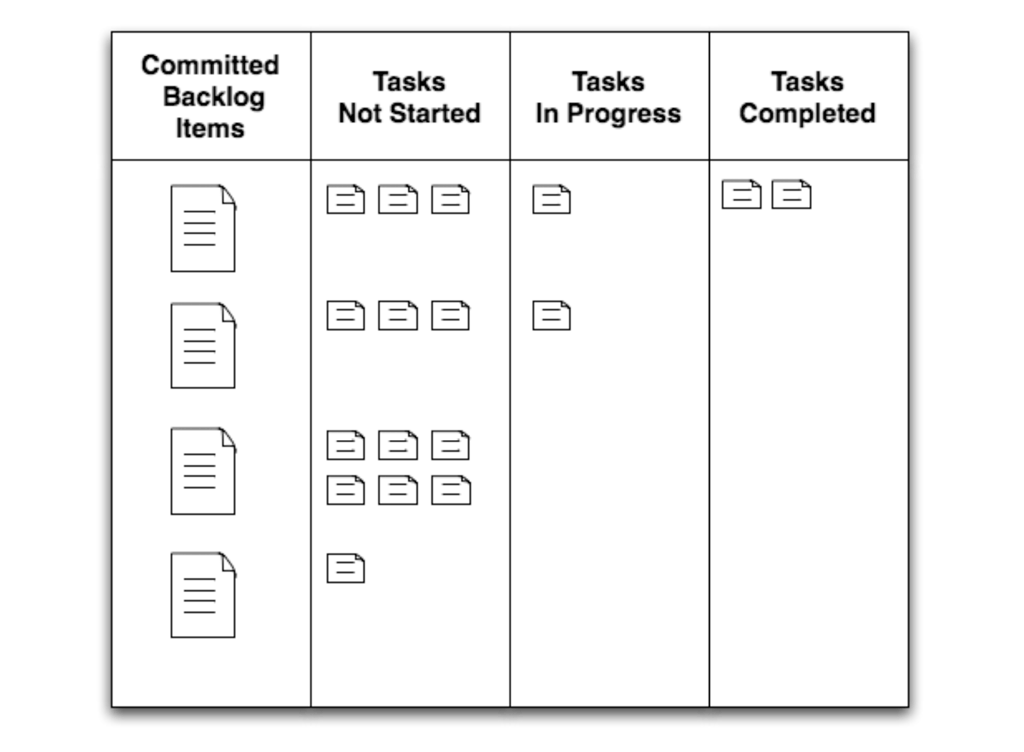

8. Sprint Backlog

Based on the priority, user stories are taken from the Product

Backlog one at a time. The Scrum team brainstorms on it, determines the

feasibility and decides on the stories to work on a particular sprint.

The collective list of all the user stories which the scrum team works

on a particular sprint is called s Sprint backlog.

9. Story Points:

9. Story Points:

Story points are quantitative indication of the complexity of a user

story. Based on the story point, estimation and efforts for a story is

determined. Story point is relative and is not absolute. To make sure

that our estimate and efforts are correct, it’s important to check that

the user stories are not big. Precise and smaller is the user story,

accurate will be the estimation.

Each and every user story is assigned a story point based on the

Fibonacci series (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13&21). Higher is the number,

complex is the story.

To be precise

- If you give 1 / 2 / 3 story point it means the story is small and of low complexity.

- If you give points as 5 / 8, it is a medium complex and

- 13 and 21 are highly complex.

Here complexity consists of both development plus testing effort

To decide a story point, brainstorming happens with in the scrum team

and the team collectively decides a story point. It may happen that

development team gives a story point of 3 to a particular story, because

for them it may be 3 lines of code change, but testing team gives 8

story point because they feel this code change will affect larger

modules so testing effort would be larger. Whatever story point you are

giving, you have to justify it. So in this situation, brainstorming

happens and the team collectively agrees to one story point.

Whenever you are deciding on a story point, keep the below factors in mind:

- Dependency of the story with other application / module,

- Skill set of the resource

- Complexity of the story

- Historical learning,

- Acceptance criteria of the user story

If you are not aware of a particular story, don’t size it.

If you see that the story point is very high, further decompose it to smaller stories.

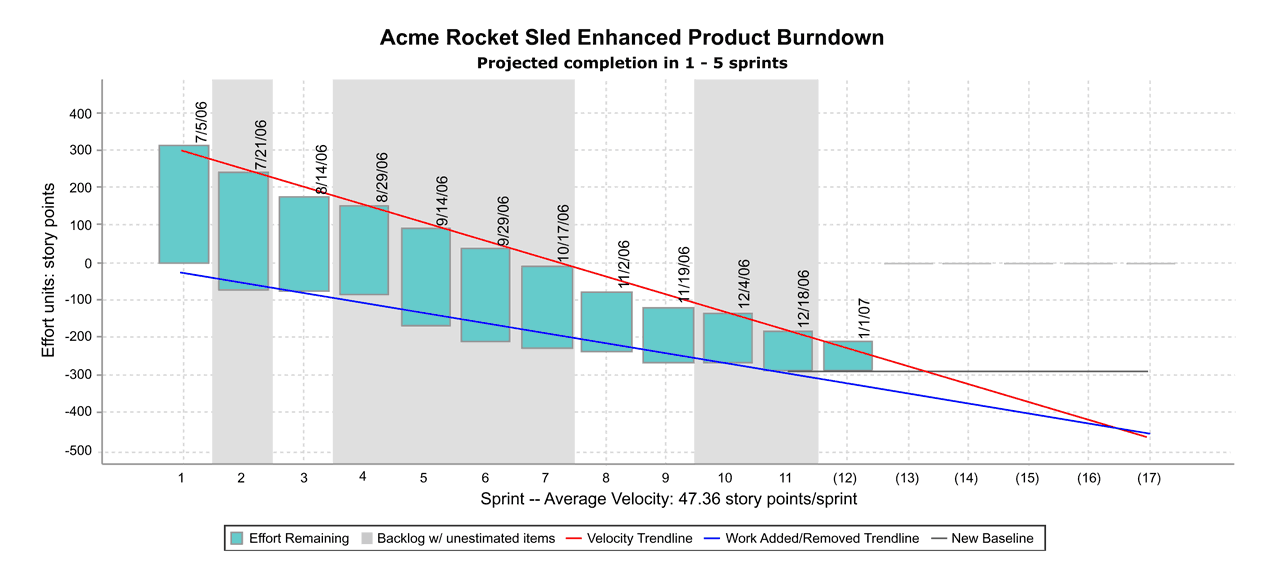

10. Burn down chart

Burn down chart is a graph which shows the estimated v/s actual effort of the scrum tasks.

It is a tracking mechanism by which for a particular sprint; day to

day tasks are tracked to check whether the stories are progressing

towards the completion of the committed story points or not.

Example: To understand this, check the below figure:

I have assumed:

I have assumed:

- 2 weeks Sprint ( 10 days)

- 2 resources actual working on the sprint.

“

Story”-> Column shows the user stories taken for the sprint.

“

Task” -> Column shows the list of task associated to the user story.

“

Effort” -> Column shows the effort. Now; this measure is

the total effort to complete the task. It does not depict the effort

put in by any specific individual.

“

Day 1 – Day 10” -> – Column(s) shows the hours which are

left to complete the story. Please see that the hour is NOT the hour

which is already done BUT the hours which are still left.

“

Estimated Effort” -> is the total of the effort. For the “Start” it is simply the sum of the entire individual task: SUM (C5: C15)

Total number of effort that has to be completed in 1 day is 70 / 10 =

7. So at the end of day 1, the effort should reduce to 70 – 7 = 63. In a

similar way it is calculated for all the days till day 10, when

estimated effort should be 0 (Row 16)

“

Actual Effort Left” -> as the name suggests, is the

effort actually left to complete the story. It may also happen that the

actual efforts increases or decreases than the estimated one.

You can use the in build functions and Chart in Excel to create this burn down chart.

Burn Down Chart steps would be:

- Enter all the stories ( Column A5 – A15)

- Enter all the Tasks ( Column B5 – B15)

- Enter the Days ( Day 1 – Day 10 )

- Enter the starting efforts (Sum the tasks C5 – C15 )

- Apply formula to calculate the “Estimated Efforts” for each day (Day

1 to Day 10). Enter the formula at D15 (C16-$C$16/10) and drag it for

all the days.

- For each day, enter the actual efforts. Enter the formula at D17

(SUM (D5:D15)) for summing up the actual efforts left, and drag it for

all the other days.

- Select it and create the chart as follows:

11. Velocity

Total number of story point which a scrum team archives in a sprint,

is called Velocity. The Scrum team is judged or referenced by its

velocity. Having said that, it should be kept in mind that the objective

here is NOT achieving the maximum story points, but to have quality

deliverable, respecting scrum team’s comfort level.

For example: For a particular sprint: total number of user stories are 8 having story points as

So here the velocity will be the sum of the story points = 30

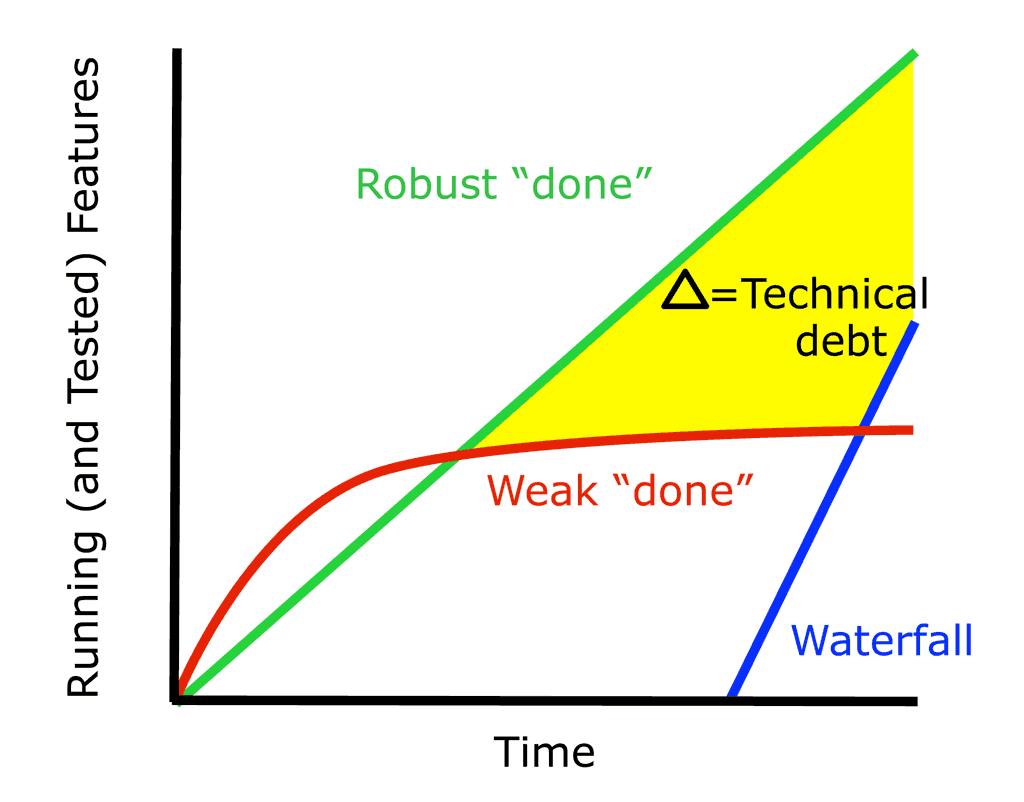

12. Definition of Done:

A story is DONE in Scrum, only when it is development and QA complete and the feature is eligible to be shipped to production.

Activities done in SCRUM Methodology:

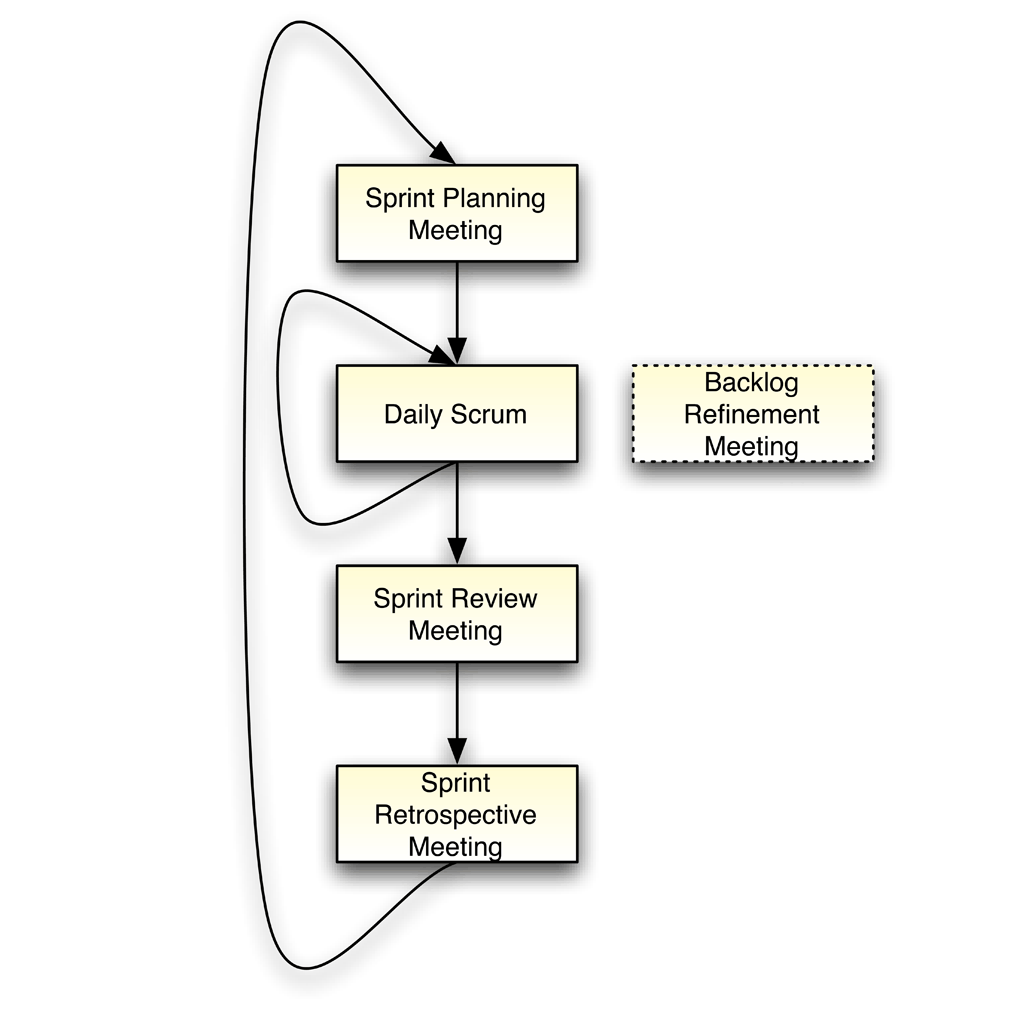

#1: Planning meeting

Planning meeting is the starting point of SCRUM. It is the meeting

where the entire scrum team gather, the product owner selects a user

story based on the priority from the product back log and the team brain

storms on it. Based on the discussion, the scrum team decides the

complexity of the story and sizes it as per the Fibonacci series. Team

identifies the tasks along with the efforts (in hours) which would be

done to complete the implementation the user story.

Many a time planning meeting is preceded by a “Pre-Planning meeting”.

It’s just like a home work which the scrum team does before they sit

for the formal planning meet. Team tries to write down the dependencies

or other factors which they would like to discuss in the planning meet.

#2: Execution of sprint tasks

As the name suggests, these are the actual work done by the scrum

team to accomplish their task and take the user story into the “Done”

state.

#3: Daily scrum meeting (call)

During the sprint cycle, every day the scrum team meets for, not more

than 15 minutes (could be a stand up call, recommended to have during

the beginning of the day) and state 3 points:

- What did the team member did yesterday

- What did the team member plan to do today

- Any impediments (roadblocks)

It is the Scrum master who facilitates this meeting. In case, any

team member is facing any kind of difficulties, the scrum master follows

up to get it resolved.

#4: Review meeting

At the end of every sprint cycle, the SCRUM team meets again and

demonstrates implemented user stories to the product owner. The product

owner may cross verify the stories as per its acceptance criteria. It’s

again the responsibility of the Scrum master to preside over this

meeting.

#5: Retrospective meeting

Retrospective meeting happens after the review meeting. The SCRUM team meets and discusses & document the following points:

- What went well during the Sprint (Best practices)

- What did not went well in the Sprint

- Lessons learnt

- Action Items.

The Scrum team should continue to follow the best practice, ignore

the “not best practices” and implement the lessons learnt during the

consequent sprints. The retrospective meeting helps to implement the

continuous improvement of the SCRUM process.

How the Process is done? An example!

Having read about the technical jargons of SCRUM; let me try to demonstrate the whole process with an example.

Step #1: Let’s have a SCRUM team of 9 people comprising of 1 product owner, 1 Scrum master, 2 testers, 4 developers and 1 DBA.

Step #2: The Sprint is decided to follow 4 weeks cycle. So we have 1 month Sprint starting 5

th June to 4

th of July.

Step #3: The Product owner has the prioritized list of user stories in the product backlog.

Step #4: The team decides to meet on 4

th June for the “Pre Planning” meeting.

- The product owner takes 1 story from the product backlog, describes it and leaves it to the team to brainstorm on it.

- The entire team discusses and communicates directly to the product owner to have clear understood of the user story.

- In a similar way various other user stories are taken. If possible team can go ahead and size the stories as well.

After all the discussion, Individual team member go back to their work stations and

- Identify their individual tasks for each story.

- Calculate the exact number of hours on which they will be working. How the member concludes these hours; let’s check that

Total number of working hours = 9

Minus 1 hour for break, minus 1 hour for meetings, minus 1 hour for mails, discussions, troubleshooting etc.

So the actual working hours = 6

Total number of working days during the Sprint = 21 days.

Total number of hours available = 21*6 = 126

The member is on leave for 2 days = 12 hours (This varies for each member, some may take leave and some may not.)

Number of actual hours = 126 – 12 = 114 hours.

This means that the member will actually available for 114 hours for

this sprint. So he will break down his individual sprint task in such a

way that total of 114 hours is reached.

Step #5: On 5

th of June the entire Scrum team meets for the “Planning Meeting”.

- Final verdict of the user story from the product backlog is done and the story is moved to the Sprint back log.

- For each story, each team member declares their identified tasks, if

required can have a discussion on those tasks, can size or resize it

(remember the Fibonacci series!!).

- The Scrum master or the team enter their individual tasks along with their hours for each story in a tool.

- After all the stories are completed, Scrum master notes the initial Velocity and formally starts the Sprint.

Step #6: Once the Sprint has started, based on the tasks assigned, each team member starts working on those tasks.

Step #7: The team meets daily for 15 minutes and discusses 3 things:

- What did they do yesterday?

- What they plan to do today

- Any impediments (roadblocks)?

Step #8: The scrum master tracks the progress on daily basis with the help of “Burn down chart”

Step #9: In case of any impediments, the Scrum master follows up to resolve those.

Step #10: On 4

th July, the team meets again for the review meeting. A member demonstrates the implemented user story to the product owner.

Step #11: On 5

th July, Team meets again for the Retrospective, where they discuss

- What went well?

- What did not went well

- Action Items.

Step #12: On 6

th July, Team again meets for the pre-planning meeting for the next sprint and the cycle continues.

Tools that can be used for SCRUM activities:

Tools that can be used for SCRUM activities:

There are many tools available which can be used extensively for tracking the scrum activities. Some of them include:

Conclusion:

In the beginning, people may face some difficulty to adopt this

methodology, but through practice you will see SCRUM doing wonders. It

keeps the resources very focused and you can actually see your

application growing.

Many a time’s organization encourages team to have few hours as

self-study and development as a scrum task and allocate few hours.

During the review, team members also demonstrate what they have studied,

and sometimes present any tool or application which they have

developed. I personally appreciate this approach as it gives the people a

chance to enhance their knowledge and also present their skills. (Well,

I have learnt Selenium through this approach only! :) )

Ref - http://www.softwaretestinghelp.com/agile-scrum-methodology-for-development-and-testing/